Capturing the Essence of War

Profilers: Michael Bachurski , Subeom Bae, and Yunhan Yang

The Interview

Saving Memory

What was your duty as a combat photojournalist in the field?

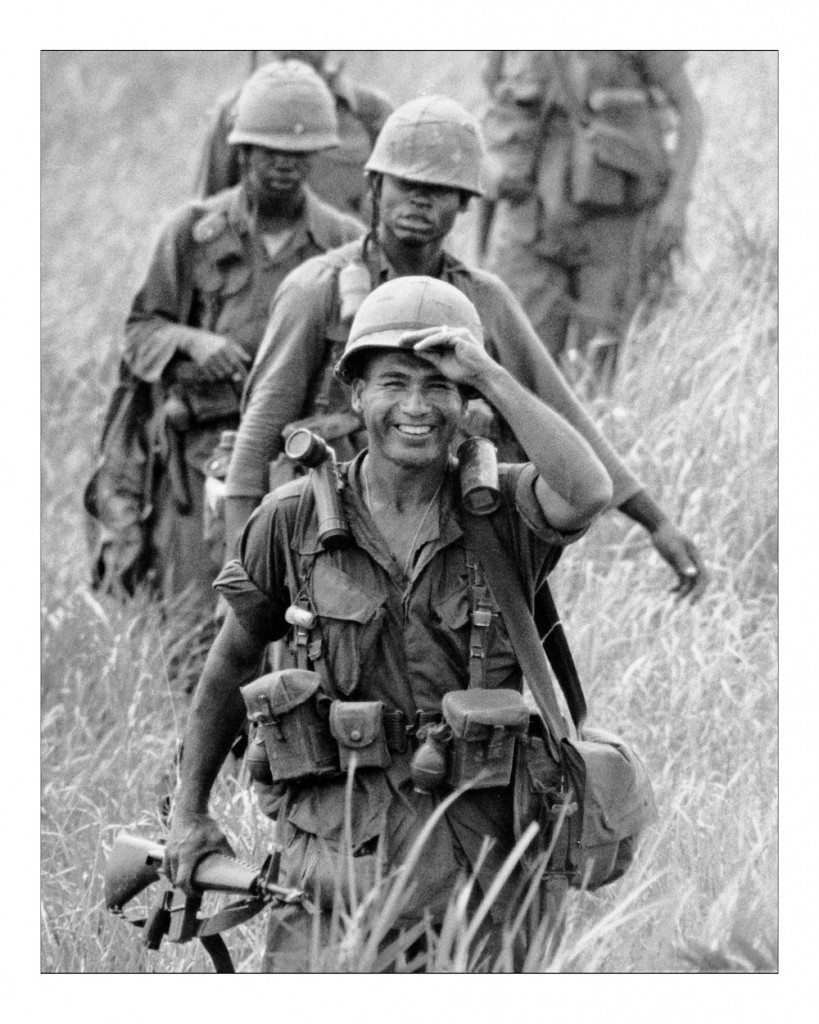

About three or four days a week, usually, my duty was to go out with a combat unit, typically an infantry company, on an air assault. An air assault means flying on a helicopter to a landing zone, a hole in the jungle usually, and you land. You hope that there’s nobody there to kill you. Sometimes we’d drop bombs on a landing strip before the first helicopters got there. I would go in with the infantry and I would walk with the infantry for anywhere from a few hours to a couple of days. I had the privilege of leaving whenever I could get out. We were re-supplied by helicopters two or three times a day. Helicopters came to take our wounded and dead out. Whenever I felt that either A, I had enough pictures, or B, I was out of film, or C, that we weren’t going to find anything, or D, that the leader of the men that I was with was crazy or stupid, I would get the next chopper out. That was most of my routine at that time.

Later on during my tour, as I became a more accomplished photographer, I began to write to news stories to go with my pictures and sometimes without pictures. I spent more and more time in garrison. Towards the middle of my tour in May of 1966, I was promoted to sergeant and I became the senior journalist in the section. By the time, our section had grown from 7 enlisted men and 2 officers to 7 officers and about 35 enlisted men. I had about 15 guys working for me.

Under Fire

Can you tell us about the time you got wounded?

I was walking with a rifle platoon down a finger of a ridge through thick elephant grass. Elephant grass is 6 to 8 feet high, very sharp edges, when you walk through it you put your arms up so your face doesn’t get cut. When you run through it you put your arms in front of you. And we came under mortar fire. A mortar round landed behind us.

The thing about mortars is that they’re indirect fire weapons and the projectiles travel in a high arc. Depending on the range, you have anywhere from 15 or 20 seconds to as much as a minute between rounds until the mortar crew gets the range. At the other end, the enemy has an observer watching you and he calls the crew or makes adjustments to the mortar to compensate for the movement or for where the round struck. So doctrine says when you come under mortar fire in the open, you run. And we did. We ran until our hearts were ready to pop out of our mouths. We were all gasping for breath. We got to the end of this finger and there was a ravine. And one at a time, we just sat down and slid down into that ravine and then we were out sight. The mortar fire couldn’t hit us.

At that point somebody came up to me and says, “Sarge, you’re bleeding.” And I said, “No I’m not.” And he said, “Yes you are.” I took my shirt off and there was a little piece of steel in my back about the size of a pencil lead and another piece in this finger right here. I didn’t feel either one of them hit. One in the back had gone through my rucksack and it went through my mess kit, which is steel. Left a hole on both ends. As it was, the medic took it out with a tweezer. Not a big deal. Could have been, but it wasn’t.

Meeting the Natives

What types of Vietnamese did you interact with during the war? And how did they feel about the war?

For the most part, the only ones that I’ve met were in the field, and for the most part, they were peasants. Not very well-educated, not very well aware of what’s going on in the larger world. Most of them greeted us neutrally. Some were quite afraid of us. Some were opportunists and they saw there was some way that they can advance themselves by being with us. So it was a mixture. I mean, at heart, they’re people just like us.

Working with Nguyen Cao Ky

So, you helped Nguyen Cao Ky, the former Southern Vietnamese prime minister, write the book, Buddha’s Child. How was that experience like, working with such a prominent figure?

I spent about a year sitting down with him almost every day for a few hours, talking about his experiences in the war. I had to write the book in first person, so I had to imagine how he might speak when I wrote this book. My sense was, he believed that Vietnam was one of the most corrupt countries in the world; it was his own country. But he thought that if he could do nothing else during his time as prime minister, and this is his phrase, he would like to bring South Vietnam to a level of corruption that was internationally acceptable. Acknowledging the fact that every government has corruption.

One of the things that first disturbed and then angered me was that on my very infrequent visits to Saigon, I would see hundreds, maybe thousands of military-age men, young Vietnamese men, riding around on Japanese motorbikes with nice haircuts selling black market goods: women, drugs, whatever they could sell, whatever they could get their hands on. And I wondered, Why aren’t these guys in uniform? And I wondered why are we over here fighting their war when they’re not. And later on I found the reason was that they came from families that were affluent enough to pay some South Vietnamese army commander to pretend that they were present for duty. They would be carried on the unit rolls as present for duty when they weren’t. And the commander pocketed their pay, sold their food and their uniforms and their weapons.

War Against the Client States

What was your perspective about the US intervention in the war and did that perspective change before and after you participated in the war?

Initially, I subscribed to the domino theory and I saw, probably correctly, that North Vietnam was a proxy for the Soviet Union and for China in this war. It was a war against a client state of the United States, South Vietnam. But of course, I came to see later on that it was much more than that and it was also less than that. There was a very strong desire on the part of the Vietnamese to unify their country.

The Withdraw and Forgiveness

What is your opinion on how the war ended?

By 1975, the South Vietnamese could fly very few of their helicopters. They had no fuel. They couldn’t even move most of their tanks. They had no fuel.

This is because despite their obligations under the treaty signed during the Paris Peace Accords, the United States Congress decided to end the re-supply and re-equipping the South Vietnamese.

Under those circumstances, it took the North Vietnamese only 40 days to take the country from the time they crossed the border. I think that was unforgivable. And the man who was responsible for pushing the South Vietnamese government to sign the Paris Peace Accords was Henry Kissinger, then US Secretary of State. Many years later when Nguyen Cao Ky ran into Kissinger at the Four Seasons in New York—this is what Ky told me—Henry came over and stuck out his hand and said, “I need to apologize.” He (Ky) said, “You can’t apologize to me, you have to apologize to all those people that you killed.” And he walked out of that restaurant.

The Return

How did you feel when you returned as a tourist to Vietnam? What changed and what didn’t?

Well, I went back in 2005 as a tourist for a press reunion. And I spent some time in what is now called Ho Chi Minh City, it was Saigon. And then I went to Hanoi, where I have never been before. What’s changed, of course, is that country is much more fluent than it ever war. People have much more money in their pockets. The rural parts hadn’t changed as much as I thought they would, but Saigon, Ho Chi Minh City, had become enormous. Americans were very popular there, but mostly because the people sought to enrich themselves from us.

Proving Self-Worth

If you could go back in time, would you serve again?

Yes because this was, for me personally, as much about a rite of passage about proving myself to myself. I’m a very short man, as you noticed. And this is not a society that looks up to short men. Looks sort of down on short men. Almost in the same way they look down on women. And it was important to me to know for my own purposes, for my own self sense of self-worth, that I had served honorably and well, and then I had done my job and then I had done it better than average. I may say so, I thought I have done it much better than average, but I had no way of knowing that. I didn’t know what would happen when the first bullet would so pass my head, whether I would shit my pants or just go do my job. I’m glad to say I didn’t shit my pants.

Sorrow of War

Was there anything you regret during the war?

I regret seeing so many of my friends killed. Very much so. That’s not the same thing as would I go back. Yes, I’d go back. I’d serve again. But I hoped that the ones who are killed didn’t. I lost a lot of good friends.

All photographs were given by Mr. Wolf to assist the profilers on this multimedia project.