Charlotte L. Dunn: Experiencing the Ripples of a War Never-Experienced

Profilers: Dylan Bentley, Mac Krause, Raymond Kuk, Josh Zhu

“Could you tell us more about your family that was involved in the war?” (0:00 – 2:07)

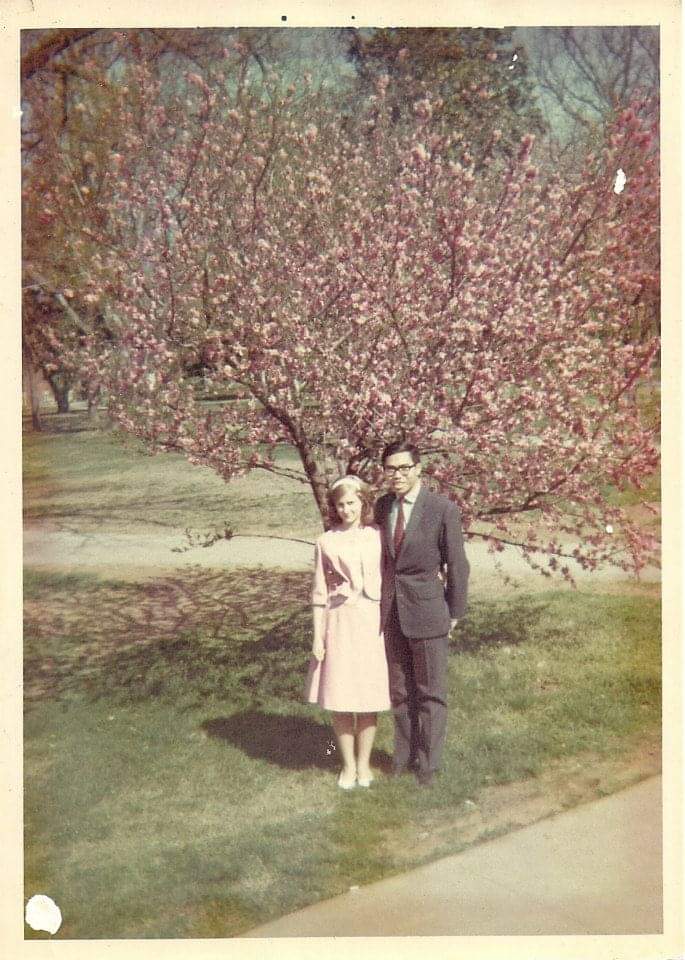

Yeah, absolutely. So, my dad comes from a small hamlet in central Vietnam called Dien Phu and he grew up in the central Highlands of Vietnam. I’m trying to think there’s so much. Dad was born in ’39 and you know he remembers the Vietnam, or the Japanese occupation, French occupation, just so many stories from my dad growing up, but he eventually. The family moved from Dien Phu to Da Nang and from Da Nang to Saigon, and he went to University of Saigon and earned 2 bachelor’s degrees by 1961. And then he went to Vanderbilt for his Master’s degree, and that’s where he met my mom, Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. He was a graduate student and mom was an undergrad. They eventually got engaged and they moved to Saigon in 1970. At that point, my dad had his doctorate from the University of Iowa and they lived in Saigon from ’70 to ’73 at which point they had to escape. And mom was pregnant with my brother, my oldest brother at that point, so they had to leave because you know, by US standards, my brother would be considered a U.S. citizen, but at that point, he would also be considered a Vietnamese citizen by the South Vietnamese government, they wouldn’t be able to leave with him.

“Do you know about their life in Saigon before they had to flee?” (2:07 – 3:11)

Yeah absolutely. So my dad, his doctoral dissertation is the basis of the [Huynh-Feldt] statistical correction, which is a modern standard of large scale assessments in statistics. So, he was considered a very valuable asset to the South Vietnamese government because he was the only person with that kind of education and degree and yeah, he had a theorem named after him. So he taught at the University of Saigon. He taught at the University of Huế. He taught at the American High School in Saigon, where a bunch of like American diplomats’ kids went and my mom taught at that same American high school, Dad taught math and Mom taught English.

“Could you share any stories that you know about their fleeing?” (3:11 – 5:59)

Yeah, absolutely. So, every year, at the end of every school year, my mom would go back to Paris, TN to stay with her parents for summer break while my dad fulfilled his mandatory military duty with the ARVN. And so, by 1973, you know, I’m sure as you’ve learned in your class, things were not going so well and my mom was pregnant, so that was an issue. So, mom put in her request to go back to Tennessee with the plan of not coming back because another thing was, because my dad was considered an asset to the South Vietnamese government, they would not let my parents leave the country at the same time. While one person was in the states, because sometimes my dad would go to the states for lectures or whatnot, the other one had to stay in the country. So, in 1973 there was a lot of issues with the government, [the] South Vietnamese government. It’s kind of chaos at that point. So, Mom applied to go back home and my dad applied to go do a Fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh. His, he had a lot of friends in the world of statistics and so he applied to go to Pittsburgh and somehow the two offices dealing with those did not compare notes. So my parents actually left on the same flight. They did not wear their wedding rings. My mom tells me that, you know, they met at my grandparents’ house and my grandfather was like, “don’t come back it’s going to get really bad. Don’t come back at all.” And so, Mom and Dad left on the same flight, pretended not to know each other. They, I think as they finally got to Tokyo and the flight from Tokyo to San Francisco, they finally put their wedding rings back on and apparently that’s the only time my dad has been tipsy. He drank a lot from Tokyo to San Francisco, and then they flew to Memphis and yeah, it was very, very scary and, yeah.

“Could you tell us about how this experience impacted them?” (5:59 – 6:53)

Yeah, so my parents definitely had, still do to a degree, maybe still do have PTSD. You know, my dad only recently, you know in his 80s, has started to share stories with me about his experience, you know with serving the ARVN with the French occupation with the Japanese occupation. And yeah, just there are times I remember my parents waking up screaming from nightmares. It’s, there’s a lot of generational trauma, for sure.

“Do you think their experiences in the war have impacted you at all?” (6:53 – 9:42)

Oh, absolutely. So it’s, you know, it’s kind of an interesting situation, because my parents didn’t have me until my dad was in his 40s and my mom was in her late 30s, so you know, and the generations are kind of stretched pretty wide in terms of years and anyhow, like growing up, I’m in South Carolina, there is not a lot of Asian people around here. At least not in the late 80s and early 90s when I was a kid, I was always the only Asian kid in class and because my mom’s white, it’s like yeah, some Asian people view me as being white. White people view me as being Asian. There’s always that feeling of being the other, but not quite the other. I was in a sorority in college and I was doing upper classmen pledging and my fellow pledge class member was Vietnamese, her family came to the United States in the late 90s from Hanoi and you know, there was one of my friends was kidding around like oh we have a Vietnamese pledge class and this girl was like oh well she’s a half breed, she doesn’t count. So there’s stuff like that and in terms of the war affecting me, I actually took a class probably not too dissimilar from the class y’all are taking. It was the Vietnam War or the US and Vietnam since 1945. And you know, we watched a lot of documentaries, we listened to a lot of guest speakers and at one point, we were watching the documentary Hearts and Minds which is a very unsettling documentary about the war that was filmed during the war, well obviously, but at one point during this class we were watching Hearts and Minds and my classmate was like, you just don’t understand what the North Vietnamese people went through. I was like, well, South Vietnam didn’t have it too easy either. So even, you know, even in the early thousands like we were kind of butting heads, you know, children of Vietnamese people and the war was, you know, a long time ago. But yeah, it definitely still affects me today.

“How do you feel depictions of the Vietnam War in films and other media compare with the experiences your parents have shared with you?” (9:42 – 10:22)

It depends on the film, you know? I think about things like Apocalypse Now and I get angry but then, you know, Hearts and Minds going back to that documentary, it’s so not how my parents experienced the war. It’s really difficult to find depictions of Vietnamese people during the war, where we’re not just a stereotype or trope.

“Do you feel as though you’re connected with Vietnam? Have you ever visited and if so, what was it like?” (10:22 – 11:46)

I have not visited. We were actually, my husband and my sister and her husband are hoping to go there next year, so that’s extremely exciting. We have never been. I do feel very connected to Vietnamese culture though. For the library, for example, I’m the librarian and I did a Vietnamese New Year story time for the kids back in January, and that was super cool. I taught them how to count. You know, we read picture books about Vietnam, although I will say it is hard to find depictions of Vietnam that are not just like about the war, even though that’s an important topic of discussion, you know, especially with picture books and children’s books. You write something that celebrates Vietnamese joy. You know, Vietnamese pain is a good thing to talk about, but Vietnamese joy is also something that needs to be seen as well and of course that representation in books is very important. Anyway, I’m sorry, I’m rambling. Could you repeat the question? I’m so sorry.

“How connected did you feel to Vietnam growing up?” (11:46 – 13:00)

Yeah, I still have a lot of family there. I think the house that my parents lived in is now a bed and breakfast in Saigon. And of course with my family I celebrate Tet and Mid Autumn Festival and all that kind of thing and we have a family altar set up and I’m connected, but it’s somewhat difficult because I don’t speak Vietnamese. That goes back to when my brother was a kid in the 70s. He was published or not published, he was punished for speaking Vietnamese in kindergarten, my parents were raising him to be bilingual and yeah, my dad just did not want to deal with, I think he was trying to look at it as like, Oh well, we should assimilate and, you know, not fight back against the status quo and plus I don’t want my kid to be punished in school for speaking Vietnamese. So he just stopped teaching him.

“Do you think your parents’ experiences and trauma have shaped your view into Vietnamese culture?” (13:00 – 14:15)

Oh, absolutely. Their view of the war is somewhat different just because Dad was not full time in the ARVN although he did have to do his summer military service and he would guard the University of Saigon at night. Just again going back to a kind of generational trauma, you know, Dad did not start telling me stories until very recently, and my mom has always told me stories. But Mom is, though she lived in Vietnam for three years, she was a civilian and she was a white woman. So, her view of certain things is very different than, you know, say my dad, or, you know, other Vietnamese family members who are there and especially those who remember, or those who stayed you know, after the fall of Saigon and were put into reeducation camps.

“Since you’re a librarian, you’re obviously around a lot of literature. Do you ever read Vietnamese literature, and if so, what are your thoughts on their depictions of Vietnamese culture?” (14:15 – 16:16)

With Vietnamese literature I’ve of course read all of your professors’ books, huge fan. His books are in terms of adult literature, because being a librarian, I’m a public librarian and I’m at a small branch so I do everything from the little kids all the way up to like senior citizens in terms of readers advisory, recommending books to them, that kind of thing. So, for adult literature, of course, you know The Sympathizer is so good. The Refugees, I found that short story collection, especially the first story, to be just so accurate of kind of the diaspora. And then in picture books and children’s books, something we talk about is windows, mirrors and doors and, you know, being able to see yourself represented and to be able to like again see people like yourself in the literature. It’s really heartwarming, in a way. When I was a kid, there weren’t very many books that I could find at the time, or that my parents could find at the time that showed Vietnamese kids and so, there’s a lot more representation in literature and a lot more positive representation in literature from what I’ve read, but I also try to avoid books that succumb to those, kind of like Asian stereotypes or Asian tropes.

“What are your critical thoughts on the Vietnam War?” (16:16 – 21:30)

Yeah, yeah, that is, that’s a good question. I realize I’m extremely biased, but I also realize, you know, having studied the war, having had so many family members affected by the war, the United States was involved for so long before it was made public and you know it feels like Vietnam was being used as a pawn between China and the USSR and then the United States, and they were just fighting this terrible war in Vietnam. And you know, they just happened to be in this country that you know and there were some that they were using to duke out their own battles and of course, the casualties are just astounding. And you think about people who are affected, like not just the Vietnamese, but the ethnic Hmong, Lao. Since Laos is considered the most bombed country in the world, they’ve had the most bombs per capita. And of course, Cambodia. I again, like I said, I’m biased because my family fought for the ARVN and when Saigon fell, my oldest uncle, who unfortunately is deceased at this point. He just died last year, but he was a high-ranking official in the ARVN was put into a reeducation camp for seven years. And then, once he was finally released, he and his family traveled across Cambodia, I believe through part of the killing fields to get to refugee camp before they could get back to, before my dad could sponsor them to come to United States.

And then one of my cousins, since after Vietnam was reunited after 75 and there was the war between Vietnam and Cambodia in the 70s and 80s. One of my cousins was actually drafted into that war and is buried in a mass grave in Cambodia. I obviously never got to meet him, but they told his mother two years after he was killed that he was in a mass grave. She had no idea where he was. So stories like this I realize it’s hard because I’m a person who likes to see both sides. I like to try to be neutral and fair, but it’s hard when your family was affected.

There is one story I do want to share, when my family was still in Dien Phu, the hamlet and the Central Highlands of Vietnam at that point, the French were patrolling during the day and the Vietnam were patrolling at night and you kind of had to play both sides. Keep them both pacified so that you know you could survive and my dad well, Mom and Dad have told me that there was this one night. They, the Vietnam planted a small explosive device under the ground in front of my grandparents’ home and the next morning the French were patrolling and one of the French soldiers stepped on the explosive device and was killed. And so the Vietnam lined up my entire family because my dad at that point was one of six children. There were more children born later, but they lined them all up and put guns to their heads and were about to kill my whole family and my grandfather, fortunately, was able to finally convince them that he had no idea about this explosive device and they were able to get out of that situation, but that’s when they left Dien Phu and left for Da Nang and just go. I realize I’m rambling, but going back to the war it, it’s hard to say how it would have played out without the American intervention, without the Soviet intervention, without the Chinese intervention. But again, it’s based on these stories I have from my family, it’s hard to stay neutral.

“Can you share any stories you know about your uncle’s experiences?” (21:30 – 25:42)

Sure. No I don’t. I’d be happy to. So my uncle was Huynh Xuan Ba he was the oldest son and he went to a special school while my dad was at the University of Saigon. My uncle went to a special school that trained government employees. I don’t, I can’t remember the name of the school right now and so he was a high-ranking official like I said, in the ARVN he was the assistant to the President of the Gia Dinh Province, I want to say. I know I don’t speak Vietnamese, my tones are terrible but he was pretty high-ranking. As such, he was able to, you know, pull quite a few favors when my parents needed them, for example, my parents were helping some of their friends adopt a child from Vietnam and you know, everything had to get signed and signed off on and approved and it just so happens that when my parents had found the child and their friends in the US needed the paperwork signed my uncle just kind of slipped the paperwork on top of the stack of stuff along with a bottle of nice liqueur and it just magically got signed off and they were able to adopt successfully, but yeah, uncle Ba was a really, he went through a lot. He was trying to get in contact with my parents in 1975. He was at the embassy in April of 75 trying to get out and could not and he was in a reeducation camp and yeah, it was hard labor and very intense, obviously, but when he got out they traveled across Cambodia. At one point my uncle told us that they were hiding in the like a house of ill repute one night in Cambodia just like staying as still as possible so the soldiers wouldn’t find them, and then when they finally got to the refugee camp and they were one of the groups that were going across because of course you had to bribe people with cash. The next group that came in behind them did not successfully get to the refugee camp, but my uncle did with his family and he came to South Carolina with his family I want to say in 87, 88, 1988 somewhere around there and he settled in Boston and lived there until he passed away last year. And he just was very, he was very proud to have served in the ARVN, he had a group of friends from Vietnam who lived in Boston and they would, you know, they had all been in reeducation camps and all served with the ARVN and they would get together like every month or so and just have like a cookout and just hang out together and share stories and reminisce.

“You mentioned about incorporating Vietnamese literature into you everyday job as a librarian. Do you ever spread your thoughts and interpretations in your day-to-day life about being Vietnamese or Vietnam war? Do you ever pass down your thoughts to your children or just people you know?” (25:42 – 27:09)

I do. I don’t have kids. I’m a, my husband and I are cat people at the moment. We hope to eventually adopt. But regarding you know, spreading awareness about Vietnamese culture and stories about, you know, my parents time in Vietnam, I do that quite a bit actually. Like for the Vietnamese story time I did at my library. I had an ao dai and wore the shoes for my wedding when my husband and I got married almost seven years ago now, we had a Vietnamese ceremony with the pig and the altar and I got like a jade necklace, which is very traditional and we wore Vietnamese outfits. I have written a little bit for my library, we have a blog where we promote book lists or holidays, and I’ve written about being Vietnamese American, and I’ve written about my dad’s experience. I’d be happy to share those links with you if you would like, but yeah, I talk about being Vietnamese lot.

“Working as a librarian, you also write, correct?” (27:09 – 27:56)

Yeah, at one point in undergrad I focused a lot on creative writing. In high school, I went to a special arts and Humanities High School where I did creative writing and yeah, I kind of write on the side. At one point I thought I would do an MFA, but I’m doing my masters of Library and information science instead. But I still write just on the side and I’ve kind of incorporated that into blog posts as I can for work.

How would you say your and your family’s lives are today in America?” (27:56 – 29:52)

Absolutely, I’d be happy to. I hate the American dream trope. Like it, well, I don’t hate it, but I have a very conflicted relationship with it because, you know, my family came to this country and prospered, they were at one point very prosperous in Vietnam, but they came here and flourished. My dad basically, as soon as he got his citizenship, because my mom was not allowed to sponsor my dad’s family to come over here, my dad had to wait until he got his citizenship to start sponsoring family members, but as soon as he could he started bringing people over. We’ve done really well here. Dad is a retired statistics professor and consultant for the federal government and various state governments and statistics and large scale assessment. And my mom is a retired Latin teacher. My siblings are doing great. My brother works for the government. My sister’s a librarian, I’m a librarian. I have so much family here. I’ve got family in Boston and Austin, TX and Southern California and you know, we joke because most of my family are pharmacists. It just happens to be something that they fell into. It’s so many cousins that are doctors and pharmacists and software engineers. Not to play to that trope, but yeah, we’ve definitely, definitely done well overall since coming to this country.

“I know that you told us about your parents having PTSD and how you remember a lot of that trauma being passed down about them, you know, screaming in terror and stuff like that. Do you ever have those feelings like day-to-day or do you just kind of like learn to live with it and just grow and just move on as a person in general?” (29:52 – 32:55)

Yeah, I think that’s an excellent question. There is definitely, I mentioned earlier you know experiencing some generational trauma just with my parents having lived what they lived through and it definitely affects me even in day-to-day life. I don’t have nightmares about it but my parents will be talking to me about something and they’ll just make some random aside and what, like? I remember in college in undergrad, my dad looked over at my boyfriend at the time was like, you know, I can assemble and disassemble and fire an M-16, right? And he was just like, and I was like, what? And yeah, going through photo albums with my parents. My dad will be like, oh, this person died in this year. This person died in this year and was all like in the, you know, it’s like this person died in the war. This person died in the war. Oh, I lost track of this person during the war and yeah, it definitely affects me. There’s the comedian Margaret Cho has this joke. It’s kind of funny, but she talks about her mom a lot and she’ll say her mom was like, oh, we didn’t have prom in Korea, only war and I, you know, we’ll talk about that joke. But then there’s this sense of like, I feel like I need to be so grateful and I am grateful to my parents for everything they’ve done for me. They are very generous, sweet people, but yeah, it’ll be like, oh, like when I was a kid. I’m like, oh, I want this doll and I’m like, oh, growing up, my dad didn’t have a pair of shoes till he was 18. You know, just I have all this, I hate to say the term blessed, but my parents have worked so hard to get where they are, and sometimes it’ll just strike me like, oh you know, my parents didn’t have nearly what I have. They didn’t have nearly what I have now when they were kids or when they were adults. And it’ll just kind of hit me sometimes and be like, wow, they worked really hard to get where they are.

2 articles by her discussing more about her personal background and heritage is linked below:

https://www.richlandlibrary.com/blog/2021-06-17/my-father-refugee

https://www.richlandlibrary.com/blog/2021-05-04/vietnamese-diaspora-and-me

POSTSCRIPT:

An excerpt from Charlotte’s article https://www.richlandlibrary.com/blog/2021-06-17/my-father-refugee:

“What he experienced there, and also guarding the University of Saigon during the school year, I may never know. He does not tell his children these things. My mother recalls seeing a man get executed for speeding in traffic during her first night in Saigon; she also remembers my father’s mother refusing to leave the bed the night the family home was raided by corrupt police officers because a small fortune’s worth of gold bars was buried beneath the floor. An elementary school on my parents’ street was bombed during the war; so was a monastery a few blocks away. These events alone left my mother with PTSD symptoms that still haunt her. My father, who remembers hiding in the central highlands of Vietnam during the Japanese invasion, does not regale me with such stories.”