Secondhand PTSD

Profilers: Nico Courts, Shawn Chang, and Diego Sansur

The Brother

Do you have any experience or background involving the Vietnam War?

I’ll just start with, as a young boy, when my brother served two tours in Vietnam – 1969 and again in 1970-71 – and I was about 10 or 11 years old at that time. So I have memories of him being there and then what was happening in this country while he was serving and how frightened my parents were and how attentive we were to watching the news every night. Then he came back, he was very much affected by the war although we didn’t know it at the time, as most families didn’t know, but slowly his life kind of unravelled. So he is very severely affected. He has PTSD, he has Agent Orange-related Leukemia, so he’s – and he’s a disabled vet, like so many others.

You said your brother was in the war. What was his job title, what was his rank, and what kind of action did he see?

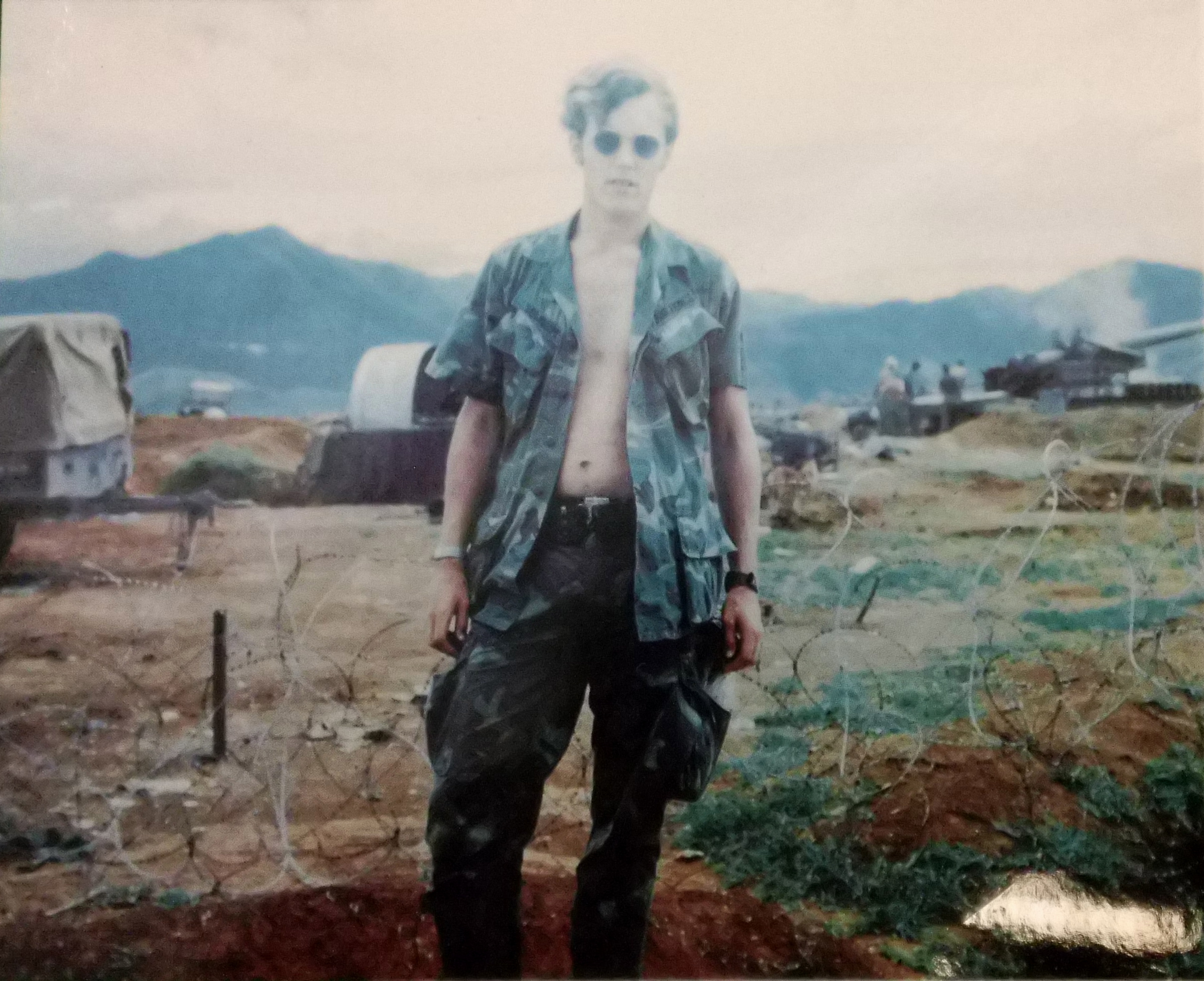

Yea he was a – and here, I’ve got a picture of him here if you guys want. This was him in 1971, just before he got out. You can tell because of the long hair. But he was a mobile radio operator in the Air Force and he worked with the infantry, he was out in the field. So he was, at one point, as close as 10-15 miles from the DMZ, which was the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam during the war. So he saw a lot of stuff happen. He wasn’t out in the jungle with an M16, but he was in his Jeep or in his radio tent communicating with the pilots. He remembers a lot of working with the Koreans, he worked with the South Korean Army, he also worked with the ARVN, the South Vietnamese army. He had some close calls and he did see a lot of carnage and terrible things happening to people.

Yea he was a – and here, I’ve got a picture of him here if you guys want. This was him in 1971, just before he got out. You can tell because of the long hair. But he was a mobile radio operator in the Air Force and he worked with the infantry, he was out in the field. So he was, at one point, as close as 10-15 miles from the DMZ, which was the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam during the war. So he saw a lot of stuff happen. He wasn’t out in the jungle with an M16, but he was in his Jeep or in his radio tent communicating with the pilots. He remembers a lot of working with the Koreans, he worked with the South Korean Army, he also worked with the ARVN, the South Vietnamese army. He had some close calls and he did see a lot of carnage and terrible things happening to people.

So he never really shot or killed anyone?

No, because that wasn’t his job, but he worked with the folks who did. He does remember taking – whenever he was on the radio, he would hear mayday calls, so that’s kind of haunting to him. He still hears those voices of the pilots going down. Usually the helicopter pilots, because he could always tell because you could hear the rotors in the background and the warbling in their voice. He said that was pretty terrible. He remembers, during one particular operation in 1971 called Lam Son 719, ARVN soldiers – South Vietnamese soldiers – were being rescued by American pilots and as they were coming back, they were flying in, and there was too many of them, so some of them were hanging on the skids of the helicopter and they couldn’t hang on any more. They were dropping to their death – he said that was horrible. He has images like that.

How was your relationship with your brother before, during, and after it was all said and done?

That’s a good question. Before it was typical – he’s nine years older than me – it was a typical big brother, little brother relationship. I wanted to follow in his footsteps and do everything he did and he would try to get rid of me because he wanted to be with his friends and do whatever they were going to do as teenagers. But it was pretty normal. I’d say we looked like, if you’ve seen the old “Leave it to Beaver” show, I was kind of like Beaver and he was like Wally – that’s kind of the way it was. When he came back from Vietnam, it was different. In fact, I remember the first day he came back: he locked himself in his room and I kept knocking on the door and he told me to go away and he didn’t want to talk to me and he didn’t want to talk to Mom. That was very unusual for him to not want to talk to Mom, because they were very close. He was withdrawn. The only person he would talk to was his friends who had been in Vietnam, they came to visit and they went into his room and were in there smoking and talking – so he was very withdrawn. I knew there was something, but we didn’t understand the full extent of it, but as the years unfolded, things got worse for him. He got into drugs and drinking and went through a couple of marriages. He had a tough time.

I remember in your book you outlined some of his letters – you could tell that he was slowly changing, right? That he was slowly changing and the world was affecting him?

Yeah, I could tell and he would try to hide the fact that he was in Vietnam. So he grew he hair long and when people asked him, he didn’t say anything. Only around other vets did he admit he was a veteran. And a lot of that was that none of them were really accepted when they came back. They weren’t accepted by society in general because we ended up losing the war – it was an unpopular war. Also, he wasn’t accepted by the World War II generation, because they figured it wasn’t a real war. Especially when the war didn’t really go the way they planned. They blamed – a lot of people blamed the veterans for that, which was unfair. That’s what I noticed, mainly, was him kind of hiding out and a lot of his friends hiding out. Then I started noticing anger outbursts and things like that that were unusual for him. He was more of a happy-go-lucky kind of person.

How did the transition go from when he left back to regular civilian life?

Well, he was going to go to college when he came back from Vietnam, but when he came back he abandoned all those ideas. I think he had trouble concentrating. So he went back into carpentry like my father, my dad was a carpenter, and he did fairly well in commercial carpentry. So that’s what he did. He seemed to be okay in terms of his work – it was his personal life and family life that was suffering. Although he did have kids and all that, eventually his drug and alcohol problems caught up with him.

In our class we have seen a couple of movies about the Vietnam War. Is there any movie character you would compare him to? Are there any similarities or resemblances?

I don’t know if there is any particular character, I mean, he was a young, naive – not soldier – airman, I guess they call them in the Air Force. Kind of like Chris Taylor in “Platoon” when he first comes to Vietnam, he’s very naive. My brother had the crisp uniform, the high and tight haircut, and everything. You can see before he left, he was wearing the John Lennon sunglasses and the peace symbol and long hair, so he transformed. He was actually, like other guys at this time, they were protesting the war while they were fighting the war in Vietnam. They did it silently, but they still – like the letters home that he wrote were different. They had peace symbols at the bottom of them, he started to question why we were here, he was telling us that there were things going on that we weren’t reading about in the newspapers back home, that we would be shocked if we knew.

Would you mind sharing with us some of those things?

Well, like us going into Laos and Cambodia, those are things that weren’t, at first, known and then were later revealed and that increased the protesting. He was referring to things like that. I think he was also referring to how we treated the Vietnamese as well – how we treated the South Vietnamese – which was not in a good way, just put it that way. Towards the end of the war, people were so bitter – the Americans were bitter, I think the South Vietnamese, many of them fighting didn’t trust the Americans, the Americans didn’t trust the South Vietnamese, and how can you fight together if you don’t trust each other? And that was the big problem. Especially that operation I mentioned earlier: Lam Son 719 – it is an example of how the Americans didn’t trust the South Vietnamese, so they didn’t give them the intelligence information they needed to conduct the operation. Then the South Vietnamese regime was corrupt and the generals were fighting so there was corruption and in-fighting going on. The result was that communists prevailed. So I think it kind of explains what went wrong. I mean, there’s a lot of complex factors, but that’s what I think he was referring to, and that he had seen a lot of people die and he was starting to wonder why. Why are the Vietnamese dying? Why are we dying? What is the purpose of this whole thing?

We’re always reading stories in the paper about soldiers who came back having flashbacks, meltdowns… Did your brother ever have anything like that?

Yea, he’s had – in fact, his most recent one was maybe five, six years ago – it was at Christmastime – and – I wasn’t there, I was here and he’s up in Seattle – apparently what happened was that he was sitting there with his family and then he was feeling kind of sad, everyone knew that he was feeling sad, and then he went into his room and he got his old boonie hat, which is like a green, floppy hat that these guys wore, and it had his dogtags and all kinds of buttons and things on it, as a lot of vets have. It’s actually from Vietnam. He brought it out and then he started to get really sad and then somebody said something and he got really pissed off and he started being very aggressive and violent. It was so bad that his wife called me up and said – right after this had happened and everything had settled down – she said “I don’t know what to do.” And I said, “Well, he’s got PTSD.” And he needs to get into a – and I had been hoping he would get into a program, so I said, “He needs to go the the VA and get some help. Get a group, get some help for what he’s doing.” Already he had sought help for cocaine addiction and alcohol addiction, but now he needed further help in terms of his PTSD. So as a result of this, he got processed through the VA and got classified as a disabled vet.

So you’re saying his wife didn’t know anything about this?

No. She knew he had been in Vietnam, but she didn’t know what PTSD was or why he would act the way he was. And the vets usually don’t help – they don’t explain it to them.

Is there any reason why? Maybe vets don’t like talking about it?

Because it’s so uncomfortable for them and, in a weird way, they’re trying to protect their families by not traumatizing them, by not telling them the worst stuff and what they’re thinking. Because they don’t, they exhibit these other negative things that actually hurt their family. PTSD – there’s something called the “second-hand smoke effect” with PTSD. If someone comes home from the war with problems, then their family can start developing problems, including young children – they can start getting symptoms of PTSD. It’s kind of like second-hand smoke: If someone smokes in the house, other people get sick too.

Carl

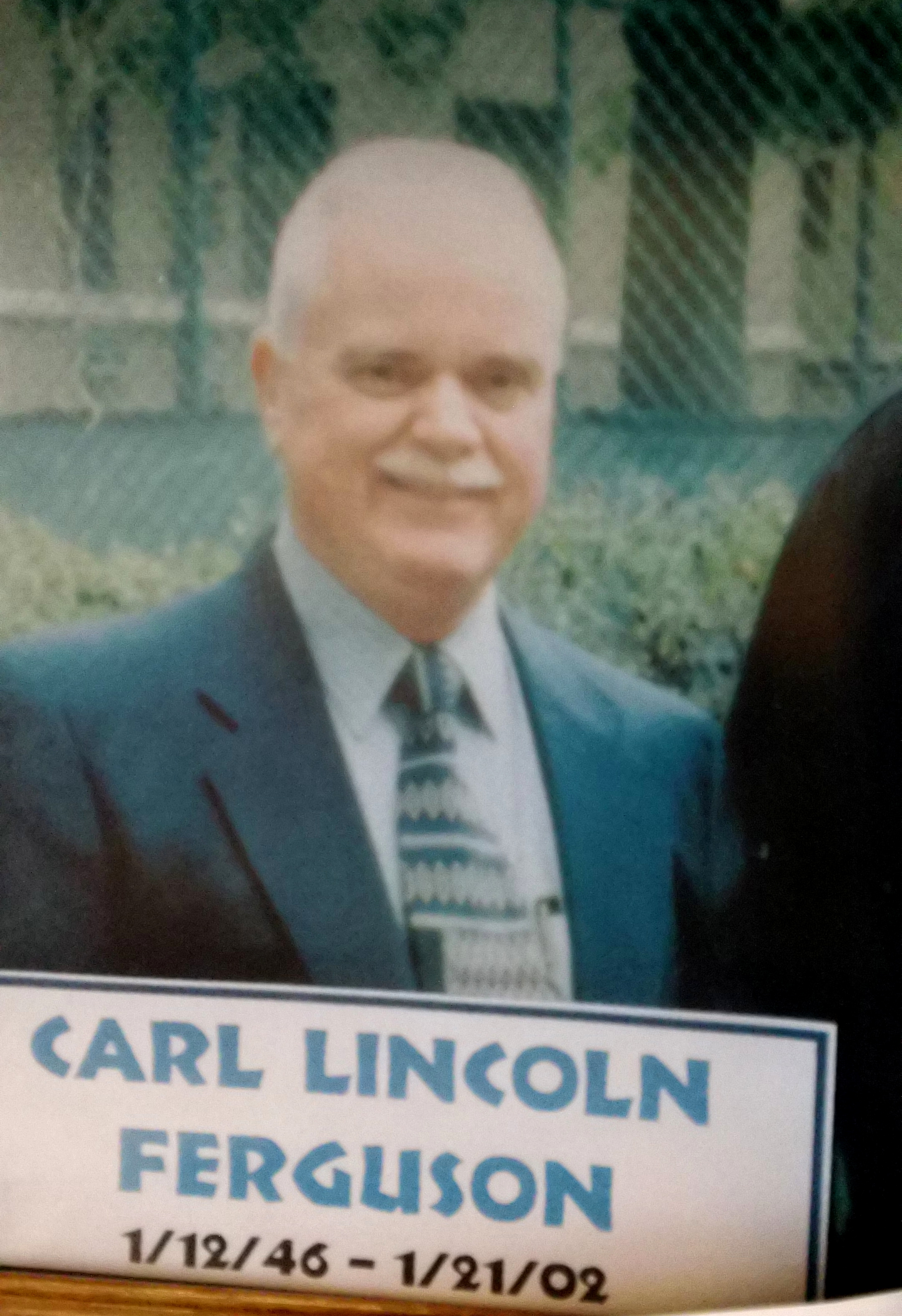

All wars are the same, basically. Like Lyndon Johnson said, “War is being asked to kill a man you don’t know well enough to hate.” It really comes down to that. And that’s going to impact your psyche – your soul – for the rest of your life. And now we know it impacts your family as well. For instance, I have that picture of my friend Carl, he’s a Vietnam vet: combat vet – Army. In 2002 he committed suicide, and he’s just one of twenty-two vets that commit suicide every day in America. 22 vets every day commit suicide. And about one to two active duty people commit suicide every day, so it’s a terrible problem. Anyways, what happened to him was that after 9/11 and we invaded Afghanistan, he was already in a PTSD group in East LA. And he started to withdraw. And I remember the last thing he told me before I found out he was dead was – he told me, “I cannot stand to see another generation lost to war,” he said, “I just can’t take it, I don’t think I can take it.” I said, “Carl, it’s going to be okay.” I was hiring him to come work on my house, he was going to do some remodeling for me, my kitchen.

All wars are the same, basically. Like Lyndon Johnson said, “War is being asked to kill a man you don’t know well enough to hate.” It really comes down to that. And that’s going to impact your psyche – your soul – for the rest of your life. And now we know it impacts your family as well. For instance, I have that picture of my friend Carl, he’s a Vietnam vet: combat vet – Army. In 2002 he committed suicide, and he’s just one of twenty-two vets that commit suicide every day in America. 22 vets every day commit suicide. And about one to two active duty people commit suicide every day, so it’s a terrible problem. Anyways, what happened to him was that after 9/11 and we invaded Afghanistan, he was already in a PTSD group in East LA. And he started to withdraw. And I remember the last thing he told me before I found out he was dead was – he told me, “I cannot stand to see another generation lost to war,” he said, “I just can’t take it, I don’t think I can take it.” I said, “Carl, it’s going to be okay.” I was hiring him to come work on my house, he was going to do some remodeling for me, my kitchen.

Then I didn’t hear from him for two or three weeks and I called up a mutual friend, another Vietnam vet, named Juan, and I said “Hey Juan,” or he prefers to be called John, I said, “John, have you heard from Carl?” and he said “No, I haven’t”. I said “I’m kind of worried about him, he was kind of depressed” and he said “Yeah, he hasn’t been in the weekly group either, I’d better go over and check on him.” So he went over to his house and found out that he had committed suicide. He had been there for almost two weeks, dead in his house. So that was pretty horrible.

So anyways, from that experience it really woke me up to this problem of suicide. I really didn’t know what to do with the story, it was so horrible, you know, what am I going to do? I’m going to tell my students. I had him on video tape so the students could watch what he had to say. So I decided I was going to go in another direction; instead of in a historical direction, to the arts. And I said, “That’s the only way I’m going to be able to tell this story.” And I thought, “Well, I’m going to write a play about it” and then I thought “that’s a great idea!” I even had an image in my mind about how it would start and everything. The only problem is that I had never written a play before [laughs] I had written books, articles as a historian, but I had never written a play. So I had to quickly learn how to do that, which is a steep learning curve. I took classes, spoke with our drama professors here, and came out with a play called “The Bronze Star” and it’s dedicated to – it’s all about – Carl’s life.

And it’s much more complicated than that. When he came back from Vietnam, not only was he rejected for being a vet, rejected as a baby-killer or whatever, but he was rejected by his family too, because he discovered while he was in Vietnam that he was gay. So when he came back, he was rejected by society for being a vet, for being gay (because this was 1969 when he came back), and also by his family, his own mother rejected him. She told him when she found out that he was gay, she said, “It would have been better for me and your father, had you died in Vietnam, than to come back and find out our son is gay.” So he was totally rejected by his mother. So that didn’t help his PTSD, obviously. And that’s the whole purpose of the play, is to show what happened to these guys when they came back, how 9/11 impacted and continues to impact people and the suicide rate and also gays in the military. It kind of deals with all those issues. Which is now, the DOD – the Department of Defense – has changed their stance completely, so now people – gays and lesbians – can serve openly. It’s a much different world now than it was in 1969.

The Veteran

So you mentioned you’ve helped hundreds of veterans to cope with their PTSD. Has there ever been a person that stands out or a point where you were scared or thought, “There’s no way I can help this guy”? Have you ever felt a person was a “lost cause”?

The only time I was ever frightened was when I first started teaching a Vietnam War course up at Greenriver Community College. This was 1994. The first day of the class, we were right in the middle of the class talking and a guy walks in, opens the door, walks in. I could tell he was in his fifties and he was real wild-eyed and kind of crazy looking and he said, “Is this the Vietnam class?” And I said, “Yeah, it is. Can I help you?” And he said, “My brother died in Vietnam. My twin brother died in Vietnam,” and he said “I was in the military too, I’m just here to see what you are doing.” And I said, “Well you can…” you know, I was trying to disarm him, “sit down”, you know? And he said, “No, I don’t know” and he started reaching behind his back like this and I was a military policeman in the military before I was a pilot, and I thought, “Oh man, he’s going for a gun.”

So I quickly jumped out in front of all the – I ran out and got by the door and got in front of him to see what I could do. Luckily, he was just nervous and he was going like that [scratches back], there was no weapon that I knew about, or at least he didn’t show me one. And he said, “I put people in the hospital over this.” And I said, “I’m really sorry to hear that, what happened?” “Well, they were impostors, you know, they pretended to know something about Vietnam and they didn’t know anything. They pretended they were veterans.” And I said, “Well, I’m a veteran. You know, I have a Ph.D. and I teach this class. My brother was in Vietnam.” He said, “Well, how do I know that’s true?”

As luck would have it, that day I had my discharge papers with me – I don’t know why I had them in my bag – I had something called a DD 214, which is the only proof you have of having been in the military. So I picked it up and I gave it to him and he looked at it and then it was like all that tension kinda [exhales] and he went like that. He handed it back to me and he said, “This is serious shit to me,” that’s what he said. And then he left, and he never came back. That was the only time I ever got scared.

Ah pls remove my name. Ty. Supawut.

I cannot believe I saw this but I was with your brother Alf in Vietnam. I was also a Ground Radio Operator trained at Keesler, and for some reason Alf Solheim is the ONLY name I remember from my tours in Vietnam; also in ‘69 and again in ‘71 and ‘72. I also am 100 percent service-connected through the VA for PTSD. My mind has so many blanks during these periods; I do know I was was in MACV, Team 98 during some of this time. Up north I was at Quang Tri, Dong Ha and Danang. If Alf or you are on FB look for Denny Miller; you’ll see me with windmills in the background and I’m wearing a stocking cap. Next time you talk to your brother tell him I say hello and he’s in my prayers. Also thanks for all you do brother.

I’m very late to this but wanted to thank you for sharing this interview with Dr Solheim. There are some parallels in my childhood with a brother 12 years older being in Berlin working with radar. Not in combat but nonetheless changed by his experience and I remember being struck by his feelings about the Vietnam war given that he is to the right of the spectrum toward America my country right or wrong. He surprised me with his sadness about the conflict in Southeast Asia and shared such feelings of regret about the great loss and waste of it all. I was very affected by Dr Solheim’s story about the man who entered his classroom ready to set things straight. How much misrepresentation of his and many vets’ experiences has held sway even to this day. One of our tragedies as a species is that generations are short enough to forget lessons we should not have to learn over and over again. To wit: Bush storming into Afghanistan so soon afterward. We learn so slowly, if we ever do.